Math, Art, and the Geometry of Wonder

This week’s exploration of mathematics and art challenged my assumptions about math being purely logical or rigid. Instead, I learned that math has long been a foundational tool for creative discovery—shaping how we see, structure, and imagine the world.

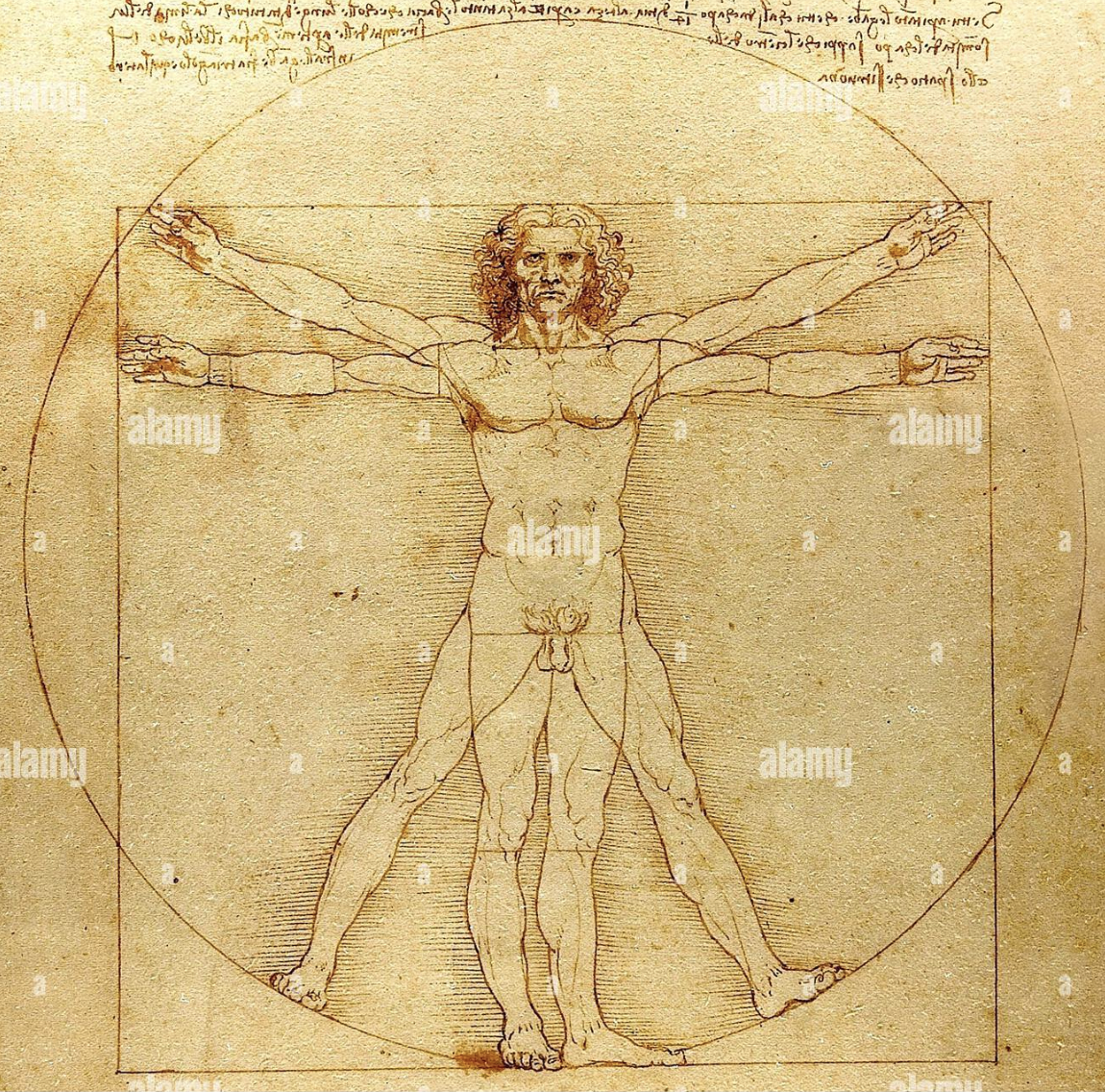

One key insight came from Matila Ghyka’s The Geometry of Art and Life, which shows how the Golden Ratio and geometric patterns have historically guided artists and architects in their pursuit of visual harmony (Ghyka 22). This reading made me realize that math isn’t just applied to art—it’s embedded within it. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, for example, isn't only a drawing—it’s a demonstration of mathematical ideals manifested through the human form.

Charles Csuri’s early computer-generated works, like Random War, amazed me in how they translate algorithmic logic into visual form. Csuri's work emphasizes that even machines, with the right code, can be used to explore randomness, emotion, and complexity (Csuri). Nathan Selikoff’s generative art, which blends mathematical formulas with motion and interaction, further emphasized how math can feel deeply alive and expressive (Selikoff).

Roy Ascott’s writing on technoetics introduced the idea that math, art, and science intersect in the realm of consciousness and spirituality (Ascott). His ideas pushed me to think of math not only as a structure but also as a portal—bridging human intuition and emerging technologies.

Ultimately, I’ve come to see mathematics, art, and science not as opposites but as overlapping lenses. Each discipline asks us to see patterns, solve problems, and reimagine possibilities. Together, they create not just answers—but wonder.

References

Abbott, Edwin A. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Dover Publications, 1992.

Ascott, Roy. “Technoetics.” Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, vol. 1, no. 1, 2003, pp. 1–5.

Csuri, Charles. “Charles Csuri: Father of Computer Art.” The Charles Csuri Project, www.charlescsuri.com. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025.

Csuri, Charles. Random Growth Drawing. 1967. The Charles Csuri Project, https://www.charlescsuri.com. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025.

Da Vinci, Leonardo. Vitruvian Man. c. 1490. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Da_Vinci_Vitruve_Luc_Viatour.jpg. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025.

Ghyka, Matila. The Geometry of Art and Life. Dover Publications, 1977.

Selikoff, Nathan. Beautiful Chaos. 2016. NathanSelikoff.com, https://www.nathanselikoff.com/project/beautiful-chaos/. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025.

Selikoff, Nathan. “Projects.” NathanSelikoff.com, www.nathanselikoff.com. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025.

Hi Reiley!

ReplyDeleteI completely agree with your perspective, and I also found it so eye opening to see how deeply intertwined mathematics and art are. Like you, I used to think of math as purely logical and rigid, but learning how it serves as a foundation for creativity has completely changed my view. The idea that math and art work together as overlapping lenses is a powerful way to look at the world!